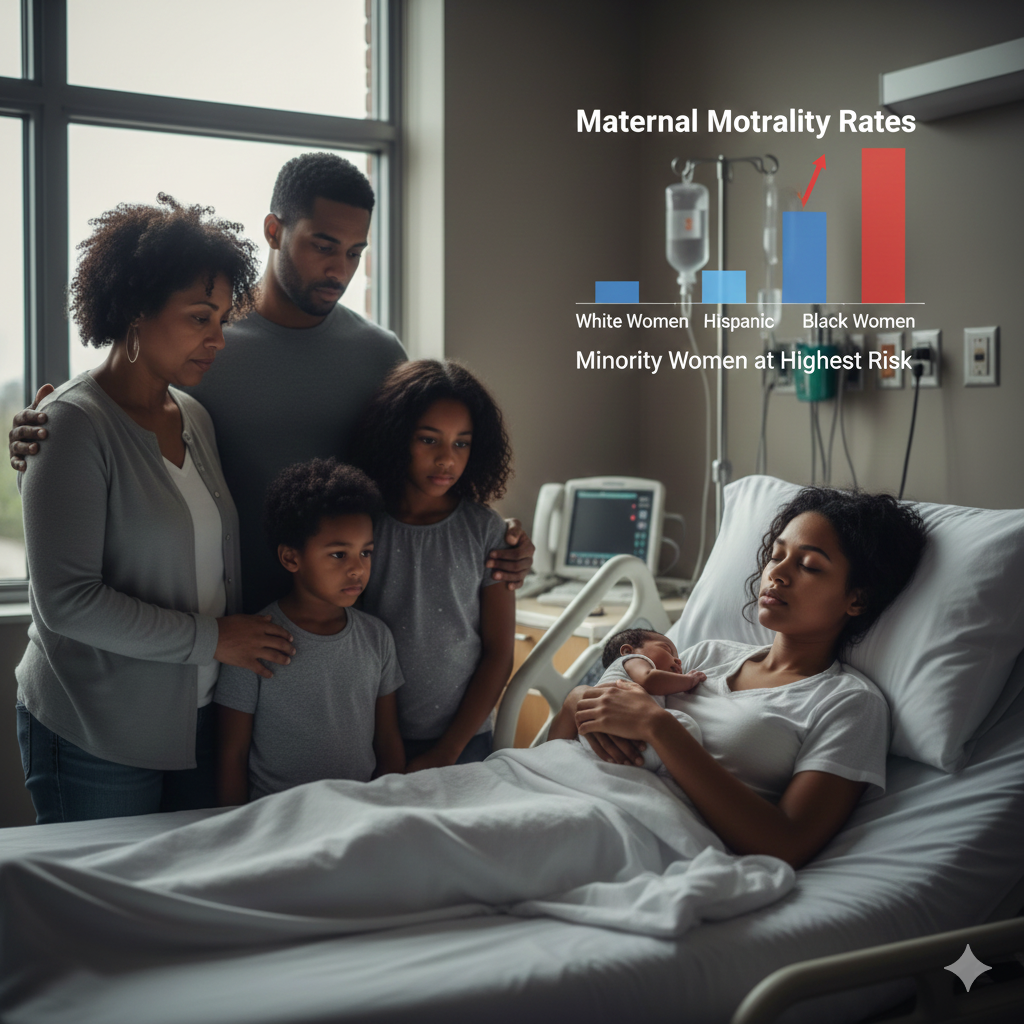

Maternal mortality should never be a normal part of childbirth—but for many minority women in Oklahoma, the reality is far darker and far more common than people realize.

According to leading public health research, Black, Native, and Hispanic mothers are at significantly higher risk of complications during pregnancy and childbirth. In Oklahoma—already one of the states with the highest maternal mortality rates in the nation—these numbers rise even more dramatically in underserved communities.

To address this crisis directly, Melika Chatman, Public Relations Coordinator for the 2nd Chance Movement Organization, sat down with Corrina Jackson, Director of Healthy Initiative Equity Birthrights, for a powerful, honest, and solution-driven conversation.

This 30–45 minute interview goes beyond statistics. It explores the human reality behind the numbers—and most importantly, what communities can do right now to protect mothers and babies.

Why Minority Women in Oklahoma Are at Higher Risk

During the interview, Corrina Jackson explains the complex factors that drive maternal mortality rates higher among minority women:

1. Lack of Access to Consistent Prenatal Care

Many mothers do not receive early and consistent prenatal checkups due to transportation issues, lack of insurance, work schedules, or mistrust in the healthcare system.

2. Implicit Bias in Medical Settings

Corrina discusses how minority women often feel unheard, dismissed, or rushed during medical appointments—leading to dangerous delays in diagnosis.

3. High Rates of Stress and Trauma

Chronic stress, especially stress related to poverty, incarceration, discrimination, and unstable housing, directly increases pregnancy-related complications.

4. Limited Health Education in the Community

When young women are not taught how pregnancy affects their bodies—or what warning signs to look for—preventable emergencies become fatal.

How We Can Educate the Community and Protect Future Mothers

Corrina and Melika highlight several solutions that community organizations, families, and individuals can take to protect mothers:

✔ Community-based education workshops

Programs teaching:

Warning signs during pregnancy

Mental health support

Healthy childbirth preparation

Breastfeeding and postpartum care

✔ Doula and birth support programs

Women supported by trained doulas experience fewer complications, shorter labor, and better outcomes.

✔ Encouraging young mothers to speak up

“Mothers need to know: Your voice matters,” Corrina says. “If something feels wrong, say it. If they don’t listen, say it again.”

✔ Expanding resources for incarcerated and justice-involved women

Melika and Corrina emphasize the importance of prenatal support for women in detention or community corrections—groups often overlooked in maternal health discussions.

✔ Healing community trust

Healthy Initiative Equity Birthrights works to rebuild trust between minority communities and healthcare providers by advocating for respectful, culturally competent care.

What Young Mothers Need to Know Right Now

Corrina gives several direct, practical warnings all young mothers should hear:

Never ignore pain, especially severe headaches, swelling, blurred vision, or shortness of breath.

You do not need permission to go to the ER.

Hydration and nutrition are critical, not optional.

Mental health changes matter just as much as physical symptoms.

Birth plans are important—but safety is always the first priority.

She also stresses that fear should not keep any woman from seeking care:

“Too many mothers think they’re being dramatic or bothering the doctor. You are not. You are protecting yourself and your baby.”

This Conversation Is Needed Now More Than Ever

Oklahoma’s maternal mortality crisis is not just a statistic—it’s a community emergency.

Organizations like the 2nd Chance Movement and Healthy Initiative Equity Birthrights are fighting every day to close the gap, educate families, empower young mothers, and give communities the tools to help save lives.

This interview is emotional, honest, and full of actionable steps that families, fathers, future mothers, and community leaders can take immediately.

If you care about the health of mothers and babies in your community, this conversation is essential.

Breaking the Cycle: Corrina Jackson on Saving Mothers’ Lives in Oklahoma’s Minority Communities

By Pubic relations coordinator Melika Chatman | November 25, 2025